Tim B.’s Rule of Three

This blogwagon had better not disqualify me from a future appearance on the Bastionland podcast…

1. Many Rats on Sticks (Skerples, 2019)

In high school, I played D&D a few times, but we barely used the rules. In college, after listening to the Adventure Zone and watching Matt Colville videos, I knew I wanted to GM, but 5E felt so stodgy. Almost immediately, I wanted to write my own rules.

Luckily, my friend Max (also my first GM, also a fellow moderator on the NSR Cauldron Discord) had found something called the GLOG thanks to the viral False Hydra.

Apparently Skerples's Rat on a Stick hack was the most comprehensive edition of the GLOG, so I had already made up my mind to hack that just days before the Many Rats on Sticks edition appeared.

I didn't care for the whole "OSR" thing, at first. I wanted player characters to feel cool and dramatic. But I figured I could start with MRoS and transform it into something more like 5E. Instead, of course, MRoS transformed me.

Looking back on MRoS now... actually, wait a minute, you have a 20% chance to be a human, an 8% chance to be an elf, gnome, or goblin (no dwarves or halflings, for some reason), and then everyone else is some kind of animal person? What the hell is this game?

Ahem... Looking back on MRoS now, what still inspires me most is how it grafts real medieval social structures onto D&D's faux-medieval setting assumptions. One of my first blog posts, "A Game to Serve the Setting", was all about this.

I've never quite liked MRoS's "solution," but it did turn me onto a problem that has troubled me for 7 years: If I'm going to design my own fantasy world, how should society in that world function? Later, reading acoup.blog deepened my conviction that something is terribly wrong with conventional fantasy.

Beyond that, MRoS's ability to make traditional fantasy feel strange and fresh and new is on par with that of Dolmenwood. There are so many weird ideas, so many fun tables, and of course, so many wizard schools! The Escaped Nun Backgrounds table is my favorite. MRoS is free and well worth reading.

2. Electric Bastionland (Chris McDowall, 2020)

I hate that this game is on this list, but it feels unavoidable.

...I should probably qualify that sentence somehow. Electric Bastionland is a genre-defining game. The NSR, let alone the NSR Cauldron, would not exist today without EB. I spent my formative years as an RPG designer picking apart every element of EB's design and putting it back together.

And yet, looking at EB now, I have very little positive to say about it. I like that it has no procedures for tracking inventory and dungeon turns; I'm apparently the last person on earth who doesn't like that Mausritter and Cairn added tracking procedures back in. But Into the Odd: Remastered is more recent, also has no tracking procedures and has aged better, I think.

There are some things I always didn't like. I think framing the PCs as failures and rejects was meant to differentiate the game from 5E D&D, but it always felt like an over-correction to me. And for all the flavor in the game's 100+ backgrounds, Bastionland never felt like a real place that I could convincingly embody as a GM. To quote Skerples's review, "the implied setting just feels like a collection [of] Capitalized Nouns."

I used to like the game's combat system (although I've never quite reconciled myself to roll-under), but in practice it's not complex enough to feel like D&D (to me) and not simple enough to get fully out of the way (for me). It turns out starting debt doesn’t reliably hook players for long-term campaigns, and the pointcrawl-creation procedures in the book seem woefully incomplete next to Mythic Bastionland. The art never quite seems to match the vibe of the text, and much of the text is rendered in hideous fake small caps.

...Would you believe, after reading all that, that my complaining is coming from a place of love? I devoured every blog post and YouTube video Chris McD made about EB, I learned everything I could possibly learn from it, and now I feel like I have to leave it behind if I'm going to grow any further. EB gave me the taste for rules-light and now I have to go lighter, lighter, lighter!

I'm reminded of Patrick Stuart's legendary, drunken EB review in which he writes that Chris McD renamed the Dungeon Master the Conductor "in an acceleration of the rule that every rpg deign head must ritually kill gary in their mind by renaming the DM into something new to symbolise their new dawn."

I think writing this section has been an exercise in ritually killing the Chris McDowall in my mind. I hope he takes it as a compliment.

3. Social Matrix Games (Chris Engle, 2023)

In 2021, Chris McDowall ran a matrix game of his own design called Sunrise Expansion. I was almost a player, but I dropped out during the first turn due to poor mental health. I will always regret it!

Chris McD’s game was based on the Matrix Games Handbook. That book focuses on rigid turn-based matrix games in which players represent competing interests – the kind of matrix game popular in military circles.

As far as I can piece together, Samuel James of the Dreaming Dragonslayer blog played in Sunrise Expansion. He dabbled in creating his own and renamed them open strategy games. Chris Engle must have taken notice, because in 2023, he sent Samuel a copy of his new book, Social Matrix Games, for review.

Little did Chris E know that, over the next two years, Samuel would transform social matrix games into his entire brand (and rename them story games for good measure).

I first encountered Sam’s take on social matrix games in the form of his scenario, Zombies Right Now. At first, I was confused. What did this have to do with the turn-based matrix games I was familiar with?

Reading the book Social Matrix Games provided an answer. Chris Engle invented matrix games and has continued to develop the concept throughout his whole life. While the earlier turn-based version caught on with the military, Chris E’s matrix games evolved to be lighter and more casual.

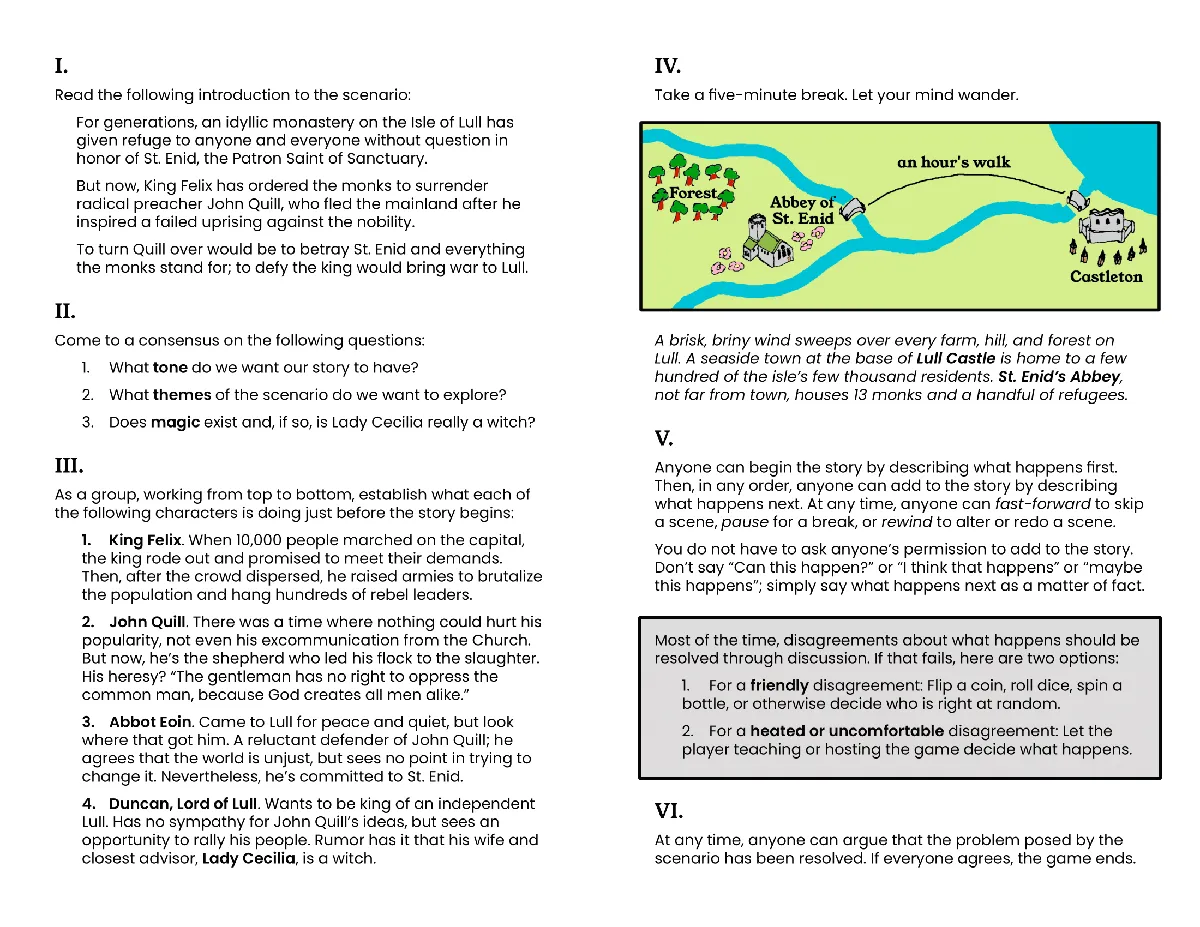

The book starts with a simple ruleset:

Matrix Game Rules: Start with a problem. Say what happens next. There is no order of play. Anyone can add to or alter what happens. All players may ask a player to roll if they don't like what they said. Roll 2d6. ≥7: The action happens and cannot be altered. ≤6: It does not happen and cannot happen in the game. The game ends when the problem is solved.

It proceeds to elaborate on those rules with over a dozen example scenarios and an example of play for each.

If you haven’t watched Sam’s video on how to play social matrix games, it’s a wonderful explanation of what makes this kind of game special. But I should probably explain why social matrix games have been so fascinating for me and why this book is on this list.

I’m currently working on a scenario called Lull Astir. I think, more than anything else I’ve made, it represents the future of how I want to engage with this hobby. I might even retroactively decide that “conversation game” and “conga” means “social matrix game” now (because come on Sam, “story game” already means something else!).

For a long time I’ve wanted to delve into deeper social, artistic, and political themes with my work. For a long time I’ve wanted to make games that I could wrangle anyone to play at a moment’s notice. And, as much as I still love problem-solvey dungeon games, I think social matrix games might be a better way to do those things.

What was your process for making your three choices?

A long and painful one. Originally I had two video games on the list but that felt like a cop out. It was hard for me to admit that there are any RPGs I like at all.

Looking back over your three picks, do you see a connection between them?

The rules get lighter and lighter as the list goes on. Two of the developers are named Chris; according to the pattern, one can only assume that Skerples’s real name is Chris as well. Also, my middle name is Christopher.

Did you have any honorable mentions?

I sometimes think Another Crab’s Treasure is the greatest video game ever made.

I love Mario games for their light and precise approach, but they have a corporate soulessness underneath. I love Dark Souls games, but their endless violence and cynicism gets old after a while.

Another Crab’s Treasure is Mario + Dark Souls. It’s just like how Spelunky combined Mario with classic roguelikes and solved the problems of both genres.

ACT’s story is surprisingly moving, not just in how it comments on contemporary social issues, but also in how it pays homage to the best moments in From Software games without resorting to parody. It understands what makes video games great in a way that stirred something deep in me more than once. More people should play it.